Phase I

The Phase I document is divided into four sections:

WASC Self Study

Introduction: Relationship to Missions, Goals and Strategies

California State University Fullerton's process to reaffirm its accreditation with the Western Association of Schools and Colleges began with the adoption of a new mission statement for the University in Fall, 1994. For 18 months, the University Planning Committee (UPC) worked on an analysis of the s trengths, w eakness, o pportunities and t hreats (a SWOT analysis) defining the University's current position. Periodic bulletins issued by the UPC invited campus response to succeeding drafts of the proposed new mission statement. The final mission statement (see Appendix 1-A) reaffirmed a widely shared campus commitment to student learning and established an organizational focus on eight specific goals designed to support the learning emphasis. Thus, the mantra, "learning is preeminent," entered the CSUF vocabulary.

For our WASC reaffirmation, the SWOT analysis is instructive because it identified, for the 1994-95 place in time, a community consensus on our learning and teaching strengths. The process was iterative. The UPC issued a "discussion document" in March, 1994, and invited campus feedback and response. The second "discussion document," released in May, 1994, contained major revisions reflecting the community’s concern with what many thought was a negative and overly simplistic assessment of strengths and weaknesses. The final analysis, issued in February, 1995, reordered some of the original items and presented a more clearly articulated set of findings. The University pointed with pride to a set of indicators that stressed its learning orientation:

-

Small class sizes

-

Direct student-professor contact, particularly in joint research projects

-

Internships, student assistantships and other experiential learning programs

-

Rich cultural diversity in and out of classrooms

-

Varied class schedules to accommodate students' needs

-

Strong community interaction, facilitating service-based learning

-

A faculty that balances teaching and research

-

Growing expertise in educational technology and communication

-

A well-equipped, safe and secure campus

-

Helpful staff

The SWOT analysis also highlighted what the campus considered to be its internal weaknesses. Among the more critical problem areas were:

-

The lack of a "distinctive image"

-

A complex, inefficient bureaucracy, perceived to be slow to make decisions

-

Declining budget support

-

Inadequate program assessment

-

Some marginal classroom facilities

-

A library collection lacking in sufficient books and periodicals

-

Support services for students

-

Under-appreciation of faculty and staff

The SWOT analysis examined opportunities and threats external to the immediate campus, highlighting the rich resources available in our major metropolitan area, our state, our alumni and our cost effectiveness, but balancing these assets with the uncertainty of the California economy, the political nature of the budget process, and a perception that there is a lack of vision and trust of higher education among the public and our elected representatives.

The SWOT analysis coincided with the development of the new mission statement for the University. Again, the process was iterative. The first draft was issued by the UPC in May, 1994, and it contained the mission statement and an unranked set of 18 goals. The second draft, in October, 1994, revised the mission statement slightly and expanded the goals to 23. This draft also contained a concept map, reproduced below, that positioned "learning" as the center of the mission.

A third draft, issued November 4, 1994, kept much of the original mission statement and organized the goals under eight themes. After minor modifications, President Gordon approved the goals on December 19, 1994, and initiated implementation to begin with the 1995-96 budget.

The mission statement reads as follows:

Learning is preeminent at California State University, Fullerton. We aspire to combine the best qualities of teaching and research universities where actively engaged students, faculty, and staff work in close collaboration to expand knowledge.

Our affordable undergraduate and graduate programs provide students the best of current practice, theory, and research and integrate professional studies with preparation in the arts and sciences. Through experiences in and out of the classroom, students develop the habit of intellectual inquiry, prepare for challenging professions, strengthen relationships to their communities and contribute productively to society.

We are a comprehensive, regional university with a global outlook, located in Orange County, a technologically rich and culturally vibrant area of metropolitan Los Angeles. Our expertise and diversity serve as a distinctive resource and catalyst for partnerships with public and private organizations. We strive to be a center of activity essential to the intellectual, cultural, and economic development of our region.

The eight goals consist of the following:

I. Ensure the preeminence of learning;

II. Provide high quality programs that meet the evolving needs of our students, community, and region;

III. Enhance scholarly and creative activity;

IV. Make collaboration integral to our activities;

V. Create an environment where all students have the opportunity to succeed;

VI. Increase external support for university programs and priorities;

VII. Expand connections and partnerships with our region;

VIII. Strengthen institutional effectiveness, collegial governance and our sense of community.

Each goal is followed by a set of strategies (see Appendix 1-A for the complete statement) designed to bring more specificity and definition to the goal. Since the adoption of the goals, the University has funded "Planning Initiatives," projects proposed by members of the university community as ways of implementing the goals and strategies. Part of our Self Study will be reviewing those initiatives as they relate to our Self-Study themes.

WASC and University Planning

Integration of planning into the assessment of university performance is a major goal for the University. The University is heavily committed to assessment of its programs. Each academic unit undertakes a seven year Program Performance Review (PPR) involving a systematic analysis of each program component and usually including a review by one or more consultants from outside the institution. (In some cases, the PPR is combined with a national accreditation. For instance, many programs in the Schools of Arts, Business Administration and Economics, Engineering and Computer Science, and Communications receive national accreditation).

In addition to PPRs and specialty accreditation self studies, all divisions in the university submit annual reports. Annual Reports are conceived as a short-term planning tool; PPRs are considered long-term. Annual reports implement goals outlined in PPRs while updating and modifying PPRs as circumstances change and new evidence emerges. Furthermore, individual centers conduct specific, more focused studies through campus surveys and other instruments as the need arises.

However, in a report prepared for the Vice President of Academic Affairs in March, 1998, the Office of Analytical Studies and the Associate Vice President for Academic Programs stated that the PPRs and Annual Reports process has been beset with several problems.

One specific criticism of annual Reports and Program Performance Reviews in the past has been that feedback following their submission has been less than hoped for by those who have labored in their preparation. Like the personnel files submitted by faculty members. . . .ARs and PPRs have often swelled to proportions that make careful reading by deans and vice presidents a daunting task.

New guidelines for Program Performance Reviews have been adopted and are currently being implemented. The changes include a requirement to do a SWOT analysis, similar to the analysis that resulted in the new University mission statement. PPRs now focus on the "Missions, Goals and Strategies" for the University and incorporate "quality indicators" and "productivity benchmarks" as part of an overall focus on assessment of programs. They are intended to be analytical and not just descriptive, with measurable outcomes and concrete results. Because the new format for PPRs is designed to cover both support and academic units, programs were invited to connect campus practices to key issues in the national higher education conversation. They are also shorter, and definitely more readable.

Several "exemplary practices" examples are documented later in this study. The Student Affairs Division conducted a self study review in 1997-98 that applied external standards established by the Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS), and linked Division practices to the University’s Mission, Goals and Strategies. This evidence constitutes the "first entry" in Phase II of the Self Study. Prior to the introduction of the new guidelines, several academic programs conducted PPR studies that were especially useful for their incorporation of assessment and outcomes measurements, and these are also noted.

Phase I of the present Self Study relies heavily on PPRs that have been compiled in the past five years. Because PPRs were not written with the Self Study as a model, we at first feared that the questions addressed by the Self Study might not be reflected in individual program self analyses. However, though some recasting of information is occasionally required, individual programs and departments have, in fact, been consistently concerned with the issues around which the Self Study is designed.

The Self-Study Proposal was written by a planning team and approved by WASC during the Fall, 1997 semester. The following recapitulates that proposal.

As described in the proposal, the institutional self study, as well as the process for drafting the self-study report, makes it a unique project for the campus. Stressing assessment based on the reflective analysis of existing and newly gathered information, the self study is intended to appraise progress in accomplishing the University’s Mission, Goals and Strategies, and documents the strengths of the University in key areas related to its Mission. The study’s three themes are drawn directly from the campus’s Mission, Goals and Strategies: Student Learning, Faculty and Staff Learning and the campus Environment for Learning, aiming through thoughtful self-assessment to develop a clearer sense of the University’s future directions and a campus-wide understanding of the implications of those directions. Tied directly to the University’s mission and intended above all to be of value for campus planning, the self study aims as well to satisfy with distinction the requirements for reaffirmation of the University’s WASC accreditation.

What makes it possible for the University to undertake the theme-based, mission-directed self study, rather than a self study like all previous such studies, focused on and organized according to the nine accreditation standards of WASC’s Handbook of Accreditation (1988) and its predecessors? A full answer is complex, yet it can be summarized simply: WASC has invited and encouraged us to conduct such an experimental self study. Ralph Wolff, Executive Director of WASC’s Accrediting Commission for Senior Colleges and Universities, has discussed on several occasions over the past two years the multiple factors leading to WASC’s invitation. Among the reasons for WASC’s change in emphasis are the following:

-

WASC is in the midst of tremendous change. It has restructured internally, and it is struggling with the implications of telecommunications and distance learning, responding to stringent new U.S. Department of Education regulations, and working on new accreditation standards and a new Handbook to be published in the year 2000.

-

WASC is attempting to respond to the same conditions of rapid change that its member institutions are facing. An important part of its strategy is to shift from being an organization that is primarily regulatory to one that is primarily service oriented. It has set up task forces and work groups to explore and implement its new orientation. It has striven to support the planning efforts of institutions, develop a user-friendly visit process, and become a vehicle for sharing good practices within the region. And, with institutions like Fullerton, whose reaccreditation is not in question, it has encouraged experimental self studies and visits.

-

WASC recognizes that it, too, must be accountable. WASC’s interactions with campuses are very expensive. A typical UC visit and preparation for it cost the campus $250,000 to $300,000. CSU self studies and visits typically cost the institutions $150,000 or more. Campuses should derive clear value from such expensive undertakings.

-

The current model of accreditation dates from the 1950s. Although over the years it has become more comprehensive and linked to strategic planning, it needs to become even more responsive to the needs of each campus. Therefore, WASC is moving from a "one-size-fits-all" model to a "tool kit" model for the self study process and report. With WASC support, recent experimental self studies and visits have occurred at CSU Sacramento, Chico, Fresno, and Humboldt and at Westmont College, Santa Clara University, Dominican College, and others. New models are also evolving for research universities like the UC, USC and Stanford.

-

In an emerging model for campus self studies, WASC’s existing standards serve as a continually present background. However, institutions that are in "good standing" with WASC, that is, have neither been placed on probation nor given only preliminary accreditation, have been encouraged to design self studies that explore themes and topics tied to the campus’s mission and that contribute to its planning efforts.

-

A key goal of such thematic, mission-based, planning-directed self studies is to foster within institutions a "culture of evidence," that is, an expectation among all campus constituencies that decisions will be based on data, that systematic assessment will be part of every program, and that claims about quality will be supported by documentation. The challenge for campuses and for WASC has always been how to validate self studies. The solution proposed is to base the self study on the assessment of evidence.

-

Traditional self studies placed heavy emphasis on documenting the material resources available to the campus, but gave little attention to the outcomes achieved with those resources, frequently ignoring student learning outcomes, perhaps hardest to assess, yet central to the purposes for which colleges and universities exist. Placing student learning at the center of a campus self study raises important questions: what are the right learning outcomes? What are the best forms of assessment? Out of the answers to questions such as these, WASC hopes to develop its new standards for 2000 and beyond.

This is the context in which WASC has offered CSUF an invaluable opportunity to use this self-study process to learn more about itself, to document its strengths, and, through the results of the self study and the responses of a WASC visiting team, gain perspectives that will be invaluable in planning its direction for the future.

Goals of CSUF’s Self Study

Two documents set the context for our self study and shape the questions that it seeks to answer: The University’s Mission, Goals and Strategies and the CSU’s Cornerstones. Of these two, the first is the most important. The campus’s articulation of its mission has now been in place for almost four years. It has shaped our discussions and guided our priorities. The timing of our self study is opportune: we need to assess how well we are doing in implementing the goals and strategies we have agreed upon. For the CSU as a whole, Cornerstones establishes goals for the coming decade that have an immediate impact on individual campus priorities. Cornerstones promises to be important to the future of the CSU and therefore to CSUF.

Themes of CSUF’s Self Study

Taking the Mission, Goals and Strategies as centrally important to CSUF’s self study, the themes of the self study are tied directly to the University’s overriding goal of being and becoming a place where learning is preeminent. What does it mean to us "to make learning preeminent," to what extent have we succeeded, and what further steps can we take to achieve this aspiration? What are the key indicators of learning that can offer us guidance into the future?

For many years, CSUF has striven to combine the best qualities of a teaching university and a research university. By tradition, as well as by emphasis in CSUF’s Mission, the University stresses not just student learning, but faculty and staff learning as well, believing that the three are integrally linked. We propose, therefore, that in focusing on learning, the self study explore three closely related themes:

Focus on Student Learning

Professor David DeVries (Communications) and a GE class on visual communication.

Using information derived from surveys, tests, focus groups, and other sources, the self study will document the University’s contributions to

-

student academic development, performance and achievement;

-

student career development;

-

student personal development; and

-

student satisfaction with their learning.

In short, we are attempting to answer the questions, "What are the ‘marks’ of the Fullerton student?" and "What are the ‘marks’ of the Fullerton graduate?" Current student and alumni voices, as well as their performance and achievement, will be sources of evidence in connection with this theme. Furthermore, this theme directs our attention not just to what students know and can do, but to how we go about determining that, thereby leading us to reconsider the methods we employ in assessing student learning and in determining program effectiveness.

Focus on Faculty and Staff Learning

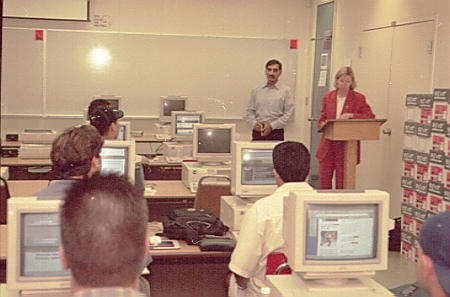

Professors Anil Puri and Jane Hall (Economics) useWEB CT to put their course, Economics 335, on line.

Using information derived from surveys, focus groups, and other sources, the self study will explore the University’s contributions to

-

the professional accomplishments and achievements of faculty and staff;

-

the professional development of faculty and staff and institutional support for it; and

-

faculty and staff satisfaction with support for learning on the campus.

The assumptions underlying this second focus are that student learning is linked inextricably with faculty and staff learning and that campus conditions fostering faculty and staff learning are an important part of what is required for the creation and support of powerful student learning communities.

Focus on the Environment for Learning

Students explore the X-ray Crystallography Facility in the Department of Chemistry

Using data from all available sources, including surveys and focus groups, the self study will explore the quality of the University’s environment for learning, both internal to the campus and in the external community, for students, faculty and staff. We will assess the quality and effectiveness of multicultural communication and interaction on campus; our evolving sense of community; and our facilities, technology, and other infrastructure for the support of learning.

By focusing on these three areas, the self study will enable us to assess our campus climate, the adaptation of the campus to and for the diversity of its students and employees, the contribution of campus governance, and the interrelations of the social and physical contexts that provide the setting for learning at the University.

For each focus, we need to

-

identify relevant data, indicators, and studies that we already have available from the past five years;

-

identify relevant assessment tools that we can employ during the next 12 months; and

-

identify events, activities, and projects planned for the next year that can contribute to the self study.

The Self Study proposal concludes by suggesting some of the available data and resources that are incorporated in the ongoing analysis of the three themes.

II. Progress thus far: The three subcommittees

Subcommittee on Student Learning

Mechanical Engineering students built a robotic device for spray-painting small parts in their senior design class.

Pat Szeszulski, Department of Child and Adolescent Studies, Chair

Members: Joe Arnold, Associate Dean, School of the Arts, Professor of Theater and Dance

Marilyn Powell Berns, Community Member

Kristine Buse, Student

David Fromson, Associate Dean, Natural Science and Mathematics, and Professor of Biology

Richard Pollard, University Librarian

Judy Ramirez, Chair, Child, Family and Community Services Division; Professor of Child and Adolescent Studies

Ephraim Smith, Vice President of Academic Affairs

Darlene Stevenson, Director, Housing and Residential Life

Dolores Vura, Director of Analytical Studies

As has been the case with all the subcommittees, the Subcommittee on Student Learning has engaged in a variety of activities in order to define the scope of its work. Members of the subcommittee have read a number of philosophical papers on student learning, gathered and considered a great deal of evidence on issues related to student learning at CSUF, and met regularly to discuss all the evidence. During this process, the subcommittee made the decision to focus on a limited number of key issues related to how to educate a diverse student body for the 21st century. Furthermore, the members decided to study each issue in great detail rather than covering all possible issues superficially. To facilitate consensus regarding which issues would be pursued, members of the subcommittee participated in a three-hour brainstorming session using Ventana GroupSystems, a software program that allows participants to contribute their ideas anonymously and simultaneously while working at separate workstations. The subcommittee’s session in the Library Studio Classroom on April 28 comprised three phases. First, 82 ideas were generated in response to the prompt, "What questions about student learning should this subcommittee examine in order to be able to address whether or not University practice is consistent with the goals of its mission?" Second, the responses were reviewed and redundant ideas were combined. Third, participants used a 5-point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) to vote whether each of the remaining 76 ideas should be considered by the committee. Independent reviews of the resultant data yielded a "philosophical/definitional" category (e.g., What is learning? What is assessment?) as well as the following four broad categories of "evidence" (particular foci) related to educating a diverse student body:

-

Who Are Our Student Learners? (Demographics; Student concerns and preparation)

-

Factors That Influence Learning (Academic &Technological resources; Student/faculty collaboration, Community-based and co-curricular experiences )

-

Learning Goals (Marks of a CSUF graduate/education; GE and selected other programs that have developed learning goals)

-

Assessment of Learning (Graduates/seniors opinions; Selected programs/departments and initiatives (e.g., Fullerton First Year) working on assessment)

The subcommittee is analyzing the four perspectives in order to address the following:

-

How students experience the University

-

How students come to understand their relation to other learners

-

The relationship between (a) and (b) and what we do in the curriculum and the classroom.

-

How assessment of (c) informs our planning for the future.

The subcommittee continues to summarize existing evidence for each of the issues and to determine which area will require further exploration.

Subcommittee on Faculty and Staff Learning

Delegation of Chinese banking executives met with faculty and students from BAE

Dave DeVries, Department of Communications, Chair

Members: Rhonda Allen, Assistant Professor of Political Science and Criminal Justice

Friedhild Brainard, Office Manager, Financial Aid

Don Castro, Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences

David Falconer, Associate Dean, Engineering and Computer Science; Associate Professor of Computer Science

Harry Gianneschi, Vice President of University Advancement

Willie Hagan, Vice President of Administrative Affairs

Jessica Medina, Student

Sandra Sutphen, Professor of Political Science

Larry Zucker, Associate Vice President of University Advancement

The Subcommittee on Faculty and Staff Learning decided quickly that many of the traditional indicators of faculty learning were good measures that stood the test of objective assessment. An enumeration of peer-reviewed publications, exhibitions, performances and conference presentations is part of the "culture of evidence" that demonstrates continued professional involvement, and presumptively, continued learning. Sources for these data are easily gathered from departmental year-end reports, Compendium announcements, and acknowledgement at the Vice President for Academic Affairs’ annual recognition day. In addition, there are numerous indicators, some easier to collect and organize than others. Among these are

-

workshop attendance

-

grants received

-

school/departmental retreats

-

new courses developed

-

active membership in professional associations

-

use of new technology

-

classes taken

The subcommittee anticipated that the Faculty Development Center will work closely with the subcommittee, both in providing data from past efforts sponsored by the Institute for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning (the Center’s predecessor) as well as informing us of new directions for faculty learning. For example, the members agreed that it would be useful to have comparative data from other institutions, especially those with a long history of formalized faculty development.

Arriving at measurements for staff learning was less straightforward. The subcommittee found some obvious indicators:

-

Classes taken at CSUF and elsewhere ("fee waiver")

-

Degrees earned while working at CSUF

-

Performance Salary Increase (PSI) awards and other recognitions

-

Workshops/conferences attended

-

Use of new technology

During its discussions about staff learning, the subcommittee felt the need for what the members called "anecdotal" material, or "data" based on responses about opportunities for learning from staff who had taken advantage of these moments. (At the same time, the subcommittee began to get a bit of feedback from some staff members about their own experiences). Because the University has recently redirected resources to provide a staff development program headed by Naomi Goodwin and Robin Innes, the subcommittee expect to find not only more courses and workshops but also more data to support the "culture of evidence" about staff learning.

The University has the results of a number of studies that have been done on campus—including some that have gathered longitudinal data—about faculty involvement in learning, but little material has been gathered in the past to document staff learning. The subcommittee anticipates that correcting this deficiency will be a high priority for its work in 1998-99.

Subcommittee on the Campus Environment for Learning

Ray Young, Department of Geography, Chair

Members: Judith Anderson, Executive Vice President

Dorothy Edwards, Human Resources

Tom Klammer, Associate Vice President for Academic Programs

John Lawrence, Professor, Management Science and Information Systems

Jeff Newell, Student

Robert Palmer, Vice President for Student Affairs

Melinda White, Physical Plant

Colleen Wilkins, Environmental Health and Safety

The campus environment for learning is a deceptively straightforward construct. To many observers the first environments which come to mind are the meso-scale "bricks and mortar" of the campus such as particular buildings or their internal classrooms and offices, and the infrastructure necessary to make those function effectively. Yet, our learning environments reach far beyond that while also operating in more subtle, behavioral domains. A full assessment of the environment for learning must include macro-level components literally from "A" (the arboretum) to "Z" (Desert Studies Center at Zzyzx).

The subcommittee also noted the importance of service and business environments that can facilitate or distract from learning. These include such components as the Admissions and Records department, Disabled Student Services office, campus food services, computer facilities and services, Library, parking, Public Safety, and the Titan Student Union. Moreover, the essence of Cal State Fullerton is expressed by its connections with the larger regional community, through which the public learns about our breadth and strengths. Those connectivity environments range from athletic events and fine arts programs to special recruitment or fundraising efforts and CLE, the Continuing Learning Experience, an organization targeted at persons desiring to pursue learning after retirement.

The subcommittee has identified more than 50 distinct components to the campus learning environment which may provide indicators of how well the university is implementing the campus Mission and Goals. After generating an extensive list of environmental components, the subcommittee arrived at a consensus about a subset that deserves closer attention for the WASC accreditation process. The subcommittee agreed upon the following rank-ordered components of the learning environment. The list combines general elements (e.g., "classrooms") with specific campus service departments and offices (e.g., Admissions and Records, Physical Plant).

-

Classrooms

-

General campus aura

-

Landscaping and pathways

-

Parking

-

Faculty offices

-

Building appearance

-

Safety elements, including campus lighting

-

Admissions and Records

-

Mission Viejo campus

-

Physical Plant and support services

-

Service areas / work rooms

-

Staff and administrative offices

-

Student services units

-

Outdoor gathering places

-

Student interactive spaces

-

Residence Halls

-

Student organizations

-

Titan Student Union

Presenting such a list quickly begs at least two interpretive questions: Do these components represent areas of concern (that is, areas of weakness) or are they components simply believed to be very important attributes of a strong university . . . or both? Could some components of the campus environment for learning have been omitted from this list because they are now perceived of as functioning quite well (such as the Library)?

While there are various sources of evidence to paint a clear picture of some of these components, the subcommittee foresees considerable research to determine how users (various groups of learners) rate the importance of, and their satisfaction with, other elements. The subcommittee plans to conduct further research, including focused surveys, during the coming months to expand knowledge about many of these themes. A reexamination of existing evidence, coupled with new perspectives, will provide a more thorough assessment to the campus and to the WASC reviewers but, just as importantly, provide planning guidance to on-campus decision-makers long after the formal WASC process has concluded.

The Culture of Evidence Internal Assessment

The University’s policy on program assessment (UPS 410.200, effective December 12, 1992) makes the faculty responsible for evaluation of academic programs. The vitality of the institution is dependent on the commitment of its faculty. One form of commitment is a willingness to evaluate candidly the programs and activities the faculty directs. Program Performance Review is a central component of the evaluation. It is based on a thorough self-study which involves the participation of the faculty. . .

The policy statement lays out the procedure for PPRs, specifying the responsibility of school deans, the option of an outside reviewer, the requirement for a seven-year plan, and the disposition of the report when it is completed. For programs that are accredited by external organizations, that accreditation report may be substituted for a PPR.

Annual reports are required from each academic unit as well. In the past, annual reports were fairly comprehensive, requiring an abbreviated vitae from each faculty member covering the year’s activities, summary statements about curriculum changes, sponsored events, student organizations and other activities including faculty publications, research, and grants. More recently, the Vice President for Academic Affairs has asked school deans to focus annual reports on specific topics, such as programs for cultural diversity and, in 1998, efforts in assessment.

To prepare evidence for the Phase I report, we read each of the PPRs prepared in the last five years (or accreditation reports where they substituted for PPRs) and the annual reviews from each school for 1998 when assessment was one of the "required" topics. We were searching for evidence of learning in our three theme areas and documentation of outcomes assessment for individual programs. What we found was a wide variety in approach to PPRs and such dissimilarity among the documents as to make comparison difficult. Some PPRs had been constructed prior to or right at the adoption of the university’s new Mission statement so a focus on mission was not present in all the PPRs we read. We created speadsheets to facilitate comparison, and included in them the categories we thought constituted the best documentation of program quality. We looked for internal and external indicators, that is, at internal self-assessment and assessment by important constituencies, such as alumni, employers, national agencies (where appropriate), faculty peers, and students. Our spreadsheets attempt to summarize our findings in the areas of overall program assessment and student learning outcomes.

We were guided in our search for evidence by a number of references, some helpful, some skeptical. Our search helped us find gaps in our evidence (to be addressed in Phase II) and areas where data exist but documentation as evidence for our three themes is less clear. Publications from WASC and the American Council on Education, as well as materials from sister campuses were especially useful.

Alexander W. Astin’s Assessment for Excellence: The Philosophy and Practice of Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, links assessment to measurement and evaluation for the purpose of what he terms "talent development." He maintains the traditional definition of excellence in higher education—what he calls the "resources" and "reputational" conceptions of excellence—are flawed because they do not "directly address the institution’s basic purposes: the education of students and the cultivation of knowledge." Resources he defines as money, high-quality faculty and high-quality students. He defines reputational as the folklore that sustains the "pecking order" of excellence where those institutions like Harvard, Yale and Berkeley are at the top and the rest of higher education somewhere below.

Astin compartmentalizes traditional assessment into the four areas of admissions, guidance and placement, classroom learning, and credentialing or certification, and then evaluates each area to uncover its contribution to "talent development" of students (we would probably call this "learning"). Only guidance and placement procedures meet his criteria for "talent development" because effective guidance and placement allow students to be assigned to classes appropriate for their level and interests. Admissions procedures, credentialing and (an added entry) faculty evaluations are not designed to help students but rather to further the reputation and resources of the institution. Admitting students with outstanding high school records and high test scores, evaluating faculty (primarily) on the basis of research publications, and seeking prestigious credentials all enhance reputation (and garner resources). Classroom teachers will be stunned to learn that Astin regards tests that measure classroom learning as a form of credentialing that does nothing to help students develop their talents. Because examinations are used primarily by instructors to assign grades, and because critical examinations are frequently given at the end of a learning period when appropriate feedback to the student is impossible, Astin finds this most common form of assessment an ineffective tool to promote student learning.

Astin’s observations interested us because most of the PPRs we read did focus strongly on the program’s reputation and resources. Typically, the PPRs stress faculty achievements in terms of research publications, external grants, or community service. Translating these into tools for developing students’ talents, or learning, is emphasized less.

An overview of assessment at the University of California, Santa Cruz written by Randy Nelson, helped define more narrowly what kinds of data are available for measurement and evaluation.

In the current jargon of education, assessment is a broad term related to the evaluation of educational effectiveness. In higher education, assessment includes activities such as studies of potential students and non-matriculants; placement and basic skills testing; surveying the educational goals and needs of new and continuing students; learning why students drop-out or transfer; evaluating the need for and effectiveness of student services; teaching and curriculum evaluation; surveys of the community; and surveys of the alumni. Although the primary focus of assessment has been the undergraduate student, evaluation activities now examine graduate students, faculty, and staff.

Nelson says that assessment may be used to improve a process (formative evaluation) or describe final outcomes (summative evaluation). Like Astin, he finds many university practices (including classroom grading) to be summative rather than formative, doing little to improve or enhance the learning experience. Nelson’s report also covers the political environment in California and the nation with respect to legislative mandates to incorporate assessment into accountability systems. He mentions specifically the report on student outcomes assessment produced by the CSU in 1989.

Student Outcomes Assessment in the California State University is a report to the Chancellor by a special advisory committee on a year-long project to solicit campus views and establish recommendations for assessment in the CSU. The report recommended the establishment of a system-wide assessment policy that should be "campus-based, faculty-centered, and student responsive." The report reflects the concern of the advisory committee that introducing new assessment techniques not add significantly to faculty workload, that they be well funded, and that student outcomes assessment "is just one of several institutional practices that must exist in order to achieve educational excellence" (page 13). The 10 member group included faculty and administrators from five CSU campuses and its suspicion about the uses of outcomes assessment is evident throughout the report. Citing political sources (the National Governor’s Association, our own State Legislature, and particularly then Assemblyman, now Senator Tom Hayden), the report acknowledged that accountability was an issue that was not going to go away.

"Higher education is a black box. You go in, and come out the other side. You don’t know what happened in it."

Tom Hayden’s analysis reflects the Legislature’s frustration with both the CSU and the UC protection of turf. In turn, the Chancellor’s office responds with mandates to do something about assessment (and accountability). Faculty respond that "we have always done assessment" and become suspicious about what the new "educational jargon" really means. The most persuasive portion of the "Final Report" presented to the CSUF Academic Senate by its Ad Hoc Committee on Assessment stresses the financial costs, increased faculty workload and unrealistic expectations that incorporating assessment will bring.

Evidence of Student Learning: Data From 1998 Annual Reports on Assessment

Suspicions aside, each school was required to submit a report on assessment of student learning outcomes as part of its annual report to the Vice President for Academic Affairs this year. What did the deans say about their schools? We can summarize quickly: Programs that rely on external accreditation use the accreditation process as a major assessment tool. Schools that house those programs are those most able to define assessment in terms of student outcomes. Specifically:

Arts: Since all four programs in Arts are nationally accredited, all have defined assessment to meet national standards. In all four programs (art, music, theater and dance), students must audition and perform in some kind of juried setting or otherwise submit their work for public critique. In several programs, external reviewers—including the local press—provide feedback to students (and faculty). "Most" art students are required to develop a portfolio for faculty review.

Business Administration and Economics: Like Arts, BAE is nationally accredited. National guidelines require the school to establish measurable assessment goals. As the school’s next accreditation does not take place until 2002, BAE intends to start developing its goals at its upcoming academic year.

Communications: Several programs in the school are nationally accredited. The Dean reported that assessment would be on the agenda for the school retreat in August, 1998. Both departments in the school indicated that a goal is to do more with assessment. The Dean listed a number of assessment tools currently in use, including student portfolios in several courses (assessed by external professionals), films (also assessed for film festivals), work on the Daily Titan, which provides public exposure and opportunities to be critiqued, internships, awards, and student competitions. The Department of Communication was re-accredited in 1998 for five years. During the process it used focus groups with students and alumni to discuss student learning outcomes and reports that it received positive feedback.

Engineering and Computer Science: Programs were reaccredited recently by their respective national associations but no assessment report was submitted this year.

Human Development and Community Service: The Dean submitted a five page report outlining assessment activities in each of the school’s divisions. Programs in education are accredited by state and national agencies. Individual programs use combinations of portfolios, capstone courses, and surveys of alumni and employers. Two programs, Counseling and Human Services, participated in the Student Learning Initiative this year to develop student learning outcomes for portions of their programs. The nursing program is preparing for its accreditation next year. Kinesiology and Health Promotion reported that assessment for its students are measured by employment rates, scores on national tests, admittance to teacher education credential programs, and high evaluations by internship supervisors (community professionals in the field).

Humanities and Social Sciences: One program in the school (the Masters of Public Administration) is nationally accredited, and was last reviewed in 1996. The Dean cited alumni surveys in five departments and a SWOT analysis in Liberal Studies. He also indicated that defining the "marks" of a Fullerton graduate had assisted in some development of measurable student outcomes. However, the dean reported no specific school or department efforts to assess student learning.

Natural Science and Mathematics: The Dean stated that "informal assessment is built into several" of the school’s programs. He cited public colloquia where students present research results, manuscripts jointly authored by faculty and students accepted for publication in peer reviewed journals, portfolio-like laboratory journals, and some exit interviews.

In summary, in 1998, schools reported some standardization in the methods used to measure student learning outcomes, including, in many places, portfolios (or portfolio-like products), public performances or presentations, alumni and employer surveys, evaluation by external reviews (either through the accreditation process, or more individually, student internships), and focus groups. However, with the exception of HDCS, no dean reported a systematic effort to identify program goals and objectives and to tie learning outcomes to those programmatic concerns. However, several deans did report that effort is on their agenda.

PPRs and evidence of learning in theme areas

We looked at PPRs to find evidence of student learning, faculty and staff learning and measures of the environment for learning. Our spreadsheets summarize our findings, but the evidence offered by individual programs is singled out to demonstrate the different approaches we found.

Student learning:

It may be easier to say what we did not find. We rarely found a focus on assessment, particularly "student outcomes assessment," even as recently as this year, with some exceptions.

The usual tools to measure student learning outcomes include standardized testing, portfolios that are faculty reviewed, comprehensive examinations, theses, capstone courses, performances—again reviewed by faculty and in some cases external reviewers—and of course classroom-based testing and grading. We found no use of standardized testing as an exit requirement, except of course for the Writing Proficiency Test required of all. We found limited use of capstone courses, theses and comprehensive examinations except at the graduate level. Portfolios, critiques and performances are common in the School of the Arts, but infrequent elsewhere. We found wide spread use of internships and other field work where students are assessed by "real world" practitioners, and wide spread evidence of student excellence through competition for awards, entrance into graduate programs, scholarships awarded, and successful employment after graduation. Representative examples, all drawn from PPRs submitted between 1993 and 1998, follow.

School of the Arts: Music

-

Students receive individualized attention regarding applied music lessons, jury process of assessment, advisement and their course of study

-

Intensive observation and internship experience in both the Music Education and Piano-Pedagogy programs

-

Formal advisement required of all undergraduates every semester

School of Business Administration and Economics: Accounting

-

Student group won a regional meet to qualify for participating in the national round of the Arthur Andersen Tax Challenge – received a Honorable Mention at the national meet

-

Of the leading accounting firms in Orange County, three of the managing partners are graduates from the CSUF Accounting Department

-

The CFO at Transamerica is a CSUF accounting alumnus

School of Communications: Communications

-

112 graduates involved in mentoring 165 seniors

-

One internship for credit is required during students’senior year

School of Human Development and Community Service: Human Services

-

10% of majors graduated with honors, high honors or highest honors during the review period

-

Internships are an integral part of the curriculum:

-

90% of majors indicate plans for graduate work

Kinesiology

-

Graduates have gone on to become athletic directors, administrators of elder-exercise programs, coaches, etc. at well-known institutions across the nation

-

Several recent graduates have gone on to Ph.D. programs

Education Division

-

Extensive commitment to multicultural education found by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE)

-

Advisement/monitoring processes in the initial credential program are fully integrated into the program

Elementary and Bilingual Education

-

Students are provided with a strong link between initial coursework and field work

Reading Program

-

Leadership skills of students are evidenced by examples of successful grant writing and consulting activities

Secondary Education

-

Students experience every aspect of teaching before actually beginning their student teaching experience

School of Engineering and Computer Science: Computer Science

-

Mandatory yearly advisement for all students

School of Humanities and Social Sciences: Afro-Ethnic Studies

-

A large number of majors are double majors

American Studies

The American Papers, a journal produced through the joint efforts of its student editorial board and the journal advisor, publishes high quality student work

- Three students awarded Graduate Equity Fellowships

- Two students awarded California Pre-Doctoral Fellowships

- During the review period, a student received the Giles T. Brown Thesis of the Year Award

- Over a dozen students have delivered papers at professional conferences

Examples of awards received by students:

-

-

-

The H&SS Life Time Achievement Award

-

The MacNeel-Pierce Oral History Scholarship

-

A University of Hawaii Historic Preservation Scholarship

-

Department recruits graduate students from a national constituency

-

-

Anthropology

-

19 graduates entered doctoral programs during the seven year review period

-

Five students were recipients of the Chancellor’s Pre-Doctoral Fellowship Award

-

Students have organized symposia for the Southwestern Anthropological Association (SWAA) meetings

-

A student won the first prize for the "Best Student Paper" at the SWAA meetings in 1994

-

Student participation in national and regional meetings of the Anthropological Association

-

In 1990, one student received the $3,000 National First Prize Award from the Lambda Alpha Anthropology National Honor Society

-

Three students received the Jenkins Award of Excellence from the Lambda Alpha Society

Chicano Studies

-

One-third of survey respondents went on to graduate school

-

30% of these respondents enrolled in a credential program

English and Comparative Literature

-

Enrollment in graduate program up 60%

-

Significant number of graduate students invited to present papers at regional, national and international conferences

-

The South Coast Poetry Journal in operation until 1995 rated by one reviewer as "among the best of the university-based literary magazines"

-

The Jacaranda Review is a journal produced by student editors in conjunction with English 408 which is a course that provides practical pre-professional experience

-

21st in the nation in graduating Hispanic-Americans with B.A.s in English

-

49th in the nation in conferring M.A. degrees on Asian-Americans

Geography

-

Graduate student ranks tripled over the previous five-year review period

-

M.A.s awarded at 60% over the previous review period

-

Five graduates delivered papers at national meetings

-

Three students continued on to Ph.D. programs

-

Four recent alumni teach geography at area community colleges

Latin American Studies

-

Dual language proficiency requirement (Spanish/Portuguese), the most rigorous of any university in California

Political Science and Public Administration

-

Several graduates chosen as Presidential Management Interns

-

Half of the surveyed alumni have completed or are enrolled in a post-baccalaureate program. Of those students who have completed, enrolled or considering graduate work, 51% have pursued the Master’s degree, 28% the pursuit of a J.D., 5% doctoral work, and 13% a teaching credential

-

In the public administration MPA program, students must demonstrate skills in at least two major computer applications upon entering the program – those lacking this knowledge must develop a plan for completion

-

An internship is required of those without administrative experience in a public sector agency in the MPA program

Psychology

-

794 students participated in independent study and directed research projects between 1987 and 1992

-

A large percentage of graduates from the master’s programs are currently enrolled in a Ph.D. program or have received a Ph.D.

-

In the academic year 1992-93 a psychology student received the President’s Associates Award and another student garnered the H&SS Life Achievement Award

-

Nearly all graduate students intend to continue in Ph.D. programs

School of Natural Science and Mathematics: Biology

-

275 graduate students involved in research during the five year review period including 25 papers with students as co-authors, 25 published abstracts, 79 papers presented

-

An average of 32 undergraduates per year participated in faculty-guided research

-

33 extramural proposals funded which specifically incorporated student research

-

92% of biology students recommended for admission to health professional schools are accepted

-

85 graduating students have been the recipients of 14 different awards during the review period

-

3 students have won a total of five research competitions

-

Biology student won the Giles T. Brown, CSUF Outstanding Thesis Award

-

Graduate program increased by about 25% during the review period

Chemistry

-

Approximately 45% of bachelor’s degree recipients enter graduate and professional programs

-

Mandatory advising program

-

24 undergraduates and 21 graduates co-authored publications with the faculty during the five year review period

-

As noted by the external reviewer, a key strength of the program is the involvement of undergraduate majors in research

-

154 undergraduates participated with faculty in research projects during 1994-95

-

53 students as co-authors at professional meetings during 1992-93

-

79 students as co-authors at professional meetings during 1993-94

Mathematics

-

Two teams of students have entered the Mathematical Competition in Modeling

-

In 1992, a mathematics student listed as a "top participant" in the Putnam Competition

-

In 1992-93, a student was awarded 2nd place in the Statewide Undergraduate Research Competition

-

In 1993-94, students won 1st and 2nd prize at the Statewide Undergraduate Research Competition

-

Student presentations at regional meetings and in statewide research competitions

-

Several Paul Douglas Scholarships ($5,000) obtained for prospective teachers from the department

Faculty and staff learning:

Acting Dean of ECS Richard Rocke and Professor David Cheng (Electrical Engineering) confer with students and representatives from Lockheed Martin about one of the 10 grants awarded for the CSU Partnership Program

Evidence from the PPRs of faculty learning invariably took the form of a compilation of the research publications, conference papers, and internal and external funding of grants by the program’s faculty members. Some programs reported that faculty had upgraded their technology skills, utilizing courses offered on campus. Others reported that faculty attended programs sponsored by the Institute for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning. Many programs reported that their faculty engaged in outside consulting, professionally related service in the community and service on campus in academic governance or as mentors. Programs could cite such evidence as development and revision of course materials and innovative pedogogical applications. But, mostly, it was publications that mattered. Those programs that received outstanding teaching awards did mention them, of course.

Learning by staff in academic departments was almost never mentioned, although many programs did acknowledge that excellent staff support contributed to the success of their programs.

The following examples are all drawn from PPRs submitted between 1993 and 1998.

Environment for Learning:

The new Anthropology offices in McCarthy Hall, refurbished by a $1,000,000 grant from NSF

Evidence relating to the campus environment for learning is the most diverse of the findings we have to report. Programs that used technology all needed upgraded equipment (these were all written before the rollout, of course). That was about the only universally shared opinion. Those programs that encouraged community -based programs and strong student support did mention those features. We don’t know if those programs that omitted such mention did so because they provide a less hospitable environment. Many programs mentioned faculty participating in mentoring. A few programs talked about outreach to community colleges and high schools. Very few mentioned strong relationships with Student Affairs programs or other resources around the campus. Several reported efforts to improve student access by soliciting money for scholarships, or obtaining research grants to support student work. This latter was especially true in the sciences.

Accreditation reports indicated that faculty are generally pleased with their physical surroundings, but PPRs rarely mentioned office space. (Kinesiology is an exception: it complained about the poor quality of its housing and surroundings.) No one talked about other amenities—or the lack of them—around the campus. Only a few even mentioned library resources.

Some sample comments:

School of the Arts: Music

-

Strong collaborative relationship with Theatre & Dance Department

-

Establishment of The Michalsky Center lab to update electronic music and associated computer equipment

-

Bands and choirs from other schools perform on campus as a way of sharing their achievements and approaches to music with CSUF students

School of Business Administration and Economics

The Business Resource Center is designed to help students successfully complete required coursework by providing tutoring in statistics, writing, accounting, finance, and economics – students also receive advisement, assistance with study skills, assessment services, and campus information. The project was funded by outside donors

Accounting

The Accounting Group, organized primarily for improvement of the curriculum and the opportunity for students and employers to interact

-

The Pacioli Club, composed of CSUF accounting alumni well-established in their professional careers, contributes substantially to the Department through referrals and mentoring

Economics

The Economics Help Center offers group tutoring, an opportunity to form study groups, and a place to seek more extensive help than might be available during office hours

-

In the High School Bridge Program, the department collaborates with three local high schools to offer Economics 100 to their advanced honors students

-

The Institute for Economic and Environmental Studies provides reports and economic forecasts to the Southern California community

-

The Center for Economic Education is a state-wide activity based at CSUF to improve economic education in California’s high schools and community colleges

School of Communications: Communications

Significant recent infusion of equipment for the television/film sequence

- The department has sponsored and organized several programs, workshops and seminars for special audiences such as high school and community college students

Speech Communications

The program collaborates successfully with a large number of hospitals, rehabilitative centers, clinics, and schools

-

The program sponsors the Communicative Disorders clinic which offers therapeutic programs to the community

School of Human Development and Community Service: Education Programs

Outreach to local high schools and community groups including much positive interaction with area school districts

-

The Anaheim Union High School Professional Center which brings together division faculty, academic department faculty, CSUF’s Center for Collaboration for Children and others an integrated services model and is referred to as an "exemplary practice" by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) review committee

Secondary Education

-

The START Program (Support and Training to Achieve the Retention of Teachers) exemplifies collaboration between the university and area school districts

-

The Center for Excellence in Science and Mathematics Education has been rated as an "outstanding" example of collaboration and support for teachers and future teachers

-

The Intern/Community Advisory Board, acting to improve teacher preparation, is an example of collaboration with the professional community

Human Services

-

Department faculty collaborate with community agencies by providing program development and evaluation, in-service training, technical assistance, and direct services

-

Periodic meetings with faculty from 5 community colleges as well as presentations about the CSUF program are conducted by the department

-

Every year, approximately seven graduate school representatives have come to speak to the majors about graduate education

-

Annual Internship Day where 120 human service agencies from the community are assembled

Kinesiology

-

The Human Performance Laboratory is a dynamic environment that functions as a student resource center

-

The Physical Performance Laboratory sponsors the Physical Performance Program providing service and public relations for both the department and the community

School of Humanities and Social Sciences: Afro-Ethnic Studies

-

Black History Month is co-sponsored by the department with a number of other campus groups. Programs are open to the community.

-

Establishment of a departmental peer-tutoring program made possible by an external grant

Anthropology

-

Department sponsors the Museum of Anthropology with changing exhibitions, open to the community

-

Respondents to student surveys report a strong "sense of family" and the bond of a close-knit community within the department

-

In conjunction with the School of Development and Human Services established a community training program called the Certificate Award in Managing Multicultural Work Environments

Chicano Studies

-

Establishment of the first Chicano/Latino Graduation recognition Banquet/Dance to honor and recognize CSUF graduates from the Chicano/Latino community

-

The Distinguished Chicano Lecture series brings outstanding Latino/Chicano celebrities and scholars to the campus

Comparative Religion

-

Good working relationships with the religion departments at the Claremont Graduate School and Chapman University

-

Department involved in presenting spring semester tours of various religious sites in the region for K-12 teachers

-

In Spring 1996, a student major visited five area high schools to speak about the relevance of the study of religion as a means towards a better understanding of other nations and cultures as well as multiculturalism in the U.S.

Geography

Students have the feeling that the Geography Department provides a "home" because of the social meeting space (Geography Lounge) which also houses the department’s maps, library and reading materials

-

Students express a "sense of community" because of the friendly supportive help of the staff and graduate assistants

-

A grant received by William Lloyd allowed for the complete makeover of the computer lab – a large increase in number of computers, up-to-date hardware and software

Political Science and Public Administration

-

The North Orange County Leadership Institute in partnership with local governments and business provides leadership training to citizens of Orange County

-

The Education Policy Fellowship Program allowed on and off-campus participants the opportunity to hear distinguished experts in the area of educational policy

Psychology

Nationally recognized Developmental Research Center

-

Nationally recognized Twins Research Center

School of Natural Science and Mathematics: Chemistry

Cultivation of partnerships with corporations such as Beckman where it has established a student internship program

- The recent opening of the Science Laboratory Center provides much improved facilities for conducting research and teaching

- Active research collaborations with several institutions including UCLA, UCI, Cal Tech, and UCR

Mathematics

Students report a real sense of community because of the rapport with faculty and staff

- A department instituted math education program aimed at minority youth in the Santa Ana Unified School District won a Golden Bell Award

- The Language and Mathematics Project (LAMP) developed to support ethnic minority school children and to give their parents the skills to help their children

- Funding received from the National Science Foundation for a Simulation Laboratory

- The Applied Statistics Laboratory and the Mathematics Education Laboratory create opportunities for collaboration between students and faculty as well as interdisciplinary interaction with students from outside the department

A note about some "exemplary practices":

As we noted earlier, most of the PPRs we examined were written before new guidelines were in place for the 1997-98 period. However, we read the PPRs of two departments, Human Services and Chemistry, that anticipated the direction of the new guidelines. We called them "exemplary practices" because they serve as models for what we hope the new reports will be.

Human Services – 1993

The PPR prepared by the Human Services Department set out in black and white what the department views as learning objectives and what measures will be used to assess achievement of those objectives. Nine broad learning objectives such as developing an understanding of the diversity within client populations and acquiring knowledge and practice skills for intervention are spelled out with specific strategies included on how to achieve these goals. Assessment measures include research and theory-based position papers, group projects which entail community/field activities, journal writing in which students gauge the impact of the course’s content on their attitudes and values, and student discussion of specific cases and field work experiences. It is worth noting that this PPR was written in 1993 before the University’s Mission and Goal statement was in effect.

Chemistry – 1995

The format of the Chemistry Department’s PPR is patterned after the University’s Mission and Goals statement. Detailed and specific narratives of how the Chemistry Department achieves each of these goals are provided. Intertwined with the narratives are the Department’s philosophies and definitions of these goals.

One means of assessing student learning is to follow the paths of students after graduation, and this department does a remarkable job of tracking graduates and alumni after leaving CSUF. As stated in the introduction, the data truly have been compiled in such a way as to be useful to the Department, School, and University in preparing proposals; involving and tracking alumni; summarizing grant, contract, and publication activity; and providing a perspective on past and future activities.

External Assessment Accreditations

The following national accrediting agencies review programs at CSUF:

| Acronym |

Name of Accrediting Organization |

Program |

|---|---|---|

| AACSB | American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business | Business |

| ABET | Accrediting Board for Engineering and Technology | Engineering |

| ACEJMC | Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communication | Communication |

| ASHA | American Speech-Language-Hearing Association | Communicative Disorders |

| CSAB | Computing Sciences Accreditation Board | Computer Science |

| NASAD | National Association of Schools of Art and Design | Art |

| NASM | National Association of Schools of Music | Music |

| NASD | National Association of Schools of Dance | Dance |

| NASPAA | National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration | MPA |

| NAST | National Association of Schools of Theater | Theater |

| NCATE | National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education | Education |

| NLN | National League of Nursing | Nursing |

Timing of accreditations occurred so that only four programs—Communications, Dance, Music, and Theater—were not reviewed during the five years we examined PPRs. For the rest, accreditation reports were substituted for PPRs, as is common, and all programs received national re-affirmation with two exceptions. The Nursing Program is treated as a "special case," below. In addition to its national accreditation, the Division of Education is also certified by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. The Educational Administration Program received "probation" from the CTC and was temporarily suspended by President Gordon to undergo restructuring which has now been completed.

Like PPRs, accrediting reports are dissimilar and generalization for all reports is difficult, though not impossible. Accrediting reports tend to be much longer and more greatly detailed than PPRs. Like PPRs, they are written for the benefit of external review teams who, when they come on campus, customarily interview faculty, administrators, students and alumni as well as undertake an examination of written reports and records. Each report is written to reflect conformity to standards established by the agency. No report was theme based. None reflected implementation of the University’s Mission and Goals except as a particular goal might have intersected with an accrediting agency’s standard.

The standards employed by most accrediting agencies focus first on program content. Does the program offer the array of courses that the agency believes necessary for certification of the program? Courses are evaluated by a comparison of syllabi and sometimes course materials such as examinations and assignments. Accrediting agencies also examine the credentials of faculty, usually confined to an examination of vita, supplemented by on-site interviews. Aside from those two indicators, the similarity among standards is less precise. While all external reviewers seek some measure of student learning and performance, criteria are not uniform. However, we did find more evidence of measurable student outcomes in programs that undergo accreditation than in those not so encumbered. Portfolios, comprehensive examinations, capstone courses, and external evaluation (for example, by internship supervisors and and by means of graded field work) were some of the tools used to assess student learning. Surveys of alumni are usually required, but surveys of employers are usually not. Active community involvement and support, and attention to fundraising are usually lower priorities. Nearly every accreditation evaluation concludes by saying that—no matter what the program—more tenure track faculty need to be hired to improve program quality. Since programs get reaccredited without these faculty (except in rare cases), we suspect the recommendation is a routine response to appease programs under evaluation.

In some cases, accreditation reports did not meet the needs of the University satisfactorily. We mention two. Because some parts of the Department of Economics offerings are accredited by AACSB, the PPR submitted by the Department in 1995, the same year as School’s accreditation, omitted an external reviewer, alumni surveys, and faculty vita. Similarly, when the Communicative Disorders program was accredited in 1997, the Department of Speech Communications submitted the report as a substitute PPR. AVP of Academic Programs Klammer noted that Communicative Disorders was only one part of Speech Communications offerings, and that "the rest" of its offerings were, therefore, not assessed.

External evaluators for PPRs

External evaluators are required in PPRs (though note the Economics exception above), and these may include off campus site teams, members from another on-campus department, or a combination of both. Most of the programs we reviewed utilized just one person, but a few—Chemistry, Mathematics, Kinesiology and Health Promotion—used a team. While on campus, the reviewer usually talks with groups of faculty, staff and students, and sometimes alumni, perhaps the dean, and reviews the written self-study materials. Our review of PPRs found external reviewers always praising the quality of instruction at CSUF, always praising the quality of the faculty, almost always commenting on the heavy teaching load, and always remarking that students give strong support to the respective programs. Constructive criticism almost always suggested seeking more external support—financial and community-based—particularly in terms of alumni relations, employing technology more creatively and more extensively, and, as mentioned, hiring more tenure track faculty. Some representative comments follow.

Foreign Languages external reviewer recommended a "re-rationalizing" of the curriculum to put greater emphasis on upper-division literature and culture/civilization courses (although that would appear to be counter to the preferences expressed by students in focus groups conducted by FLL).

Chicano Studies’ external reviewer recommended that curriculum development and faculty development should be tied tightly together, urging that faculty attend conferences to stimulate creative thinking.

External evaluation of the Geography Department noted its high level of collegiality and strong commitment to teaching. The evaluator urged greater use of GIS technology and quantitative methods, and the Department responded by adding a new course specifically in quantitative applications and increasing its technical support in laboratories.

Reviewing the Latin American Studies program, the external evaluator found the major generally rigorous but suggested that a capstone seminar and an introductory course would provide depth. While the interdisciplinary nature of the program provided a strong core faculty support, the reviewer recommended finding some way to house faculty together to permit greater interaction.

The level and quality of alumni surveys varied from recording informal conversations with a representative sample of alumni to the sophisticated analysis mentioned earlier by the MPA program. However, the findings are uniform if the methods are not. Almost invariably, alumni give their programs the highest possible marks in terms of excellent teaching, dedicated faculty, and a quality program. Criticisms, when they occur, suggest greater attention needs to be paid to career development at the undergraduate level. Several programs (American Studies, Political Science) seem to develop "better" rapport with their graduate than undergraduate students and that rapport carries over to graduate alumni support. We suspect that findings from alumni surveys are so uniformly positive because most surveys are done with mailed questionnaires. The alumni who return them are probably those who feel good about the program. Those who were disappointed are less likely to respond.

Some of the material from the sample of responses reported below also appears in our earlier summary of evidence gleaned from the PPRs.

Chicano Studies conducted a survey of alumni who graduated between June, 1988 and June, 1992 for its PPR (submitted in 1994). The largest percentage of respondents are teaching in Orange and Los Angeles County, many hired as bilingual instructors. Other positions included social services and court interpreter. One third of the graduates were in a graduate program and another 30 percent were in a credential program.

Political Science’s (1996) survey of its alumni reported that 91 percent of its graduates rated the quality of the major as excellent or good, and that half of those alumni have completed or are enrolled in a post-baccalaureate program. Of those, 50 percent pursued a masters degree, 28 percent a J.D., 5 percent doctoral work, and 13 percent a teaching credential. Alumni assessed the skills acquired in the major, citing better writing, more effective communications, and analytical tools useful in their present work situations.

National reports